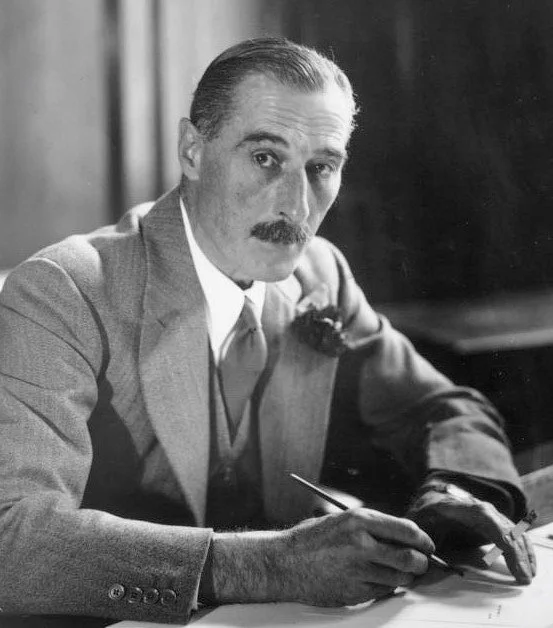

Britain's Hapless Ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson

The most popular chapter in Everybody Knows a Salesman Can’t Write a Book seems to be “11 Men With Whom it Would be Agreeable to Drink a Pint.” That chapter was inspired by a story from Winston Churchill’s distant past. After perhaps being denied membership in a dining club called The Club (there is some dispute about whether the denial ever occurred), Winston Churchill and his good friend F.E. Smith undeniably started a club of their own which they named The Other Club. The standards for selection to this invitation-only club included: “men with whom it would be agreeable to dine.”

As I’ve continued my research and writing, I’ve learned the stories of other men and women who strike me as being pint-worthy. One man stands out as such a paragon of hapless ineptitude that he would have been a fascinating drinking partner … although my side of the conversation would probably have been limited to the repeated question: “What?!??

In January 1937, Britain’s Ambassador to the Argentine Republic received a telegram from Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden offering him the post of Ambassador to Hitler’s Germany. Nevile Henderson’s reactions included “a sense of my own inadequacy” and that “it could only mean that I had been specially selected by Providence with the definite mission of, as I trusted, helping to preserve the peace of the world.”

Picture Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-C06536 / Dorneth / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de,

Henderson, who had only a basic familiarity with the German language, packed a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf to read on the ocean passage from Argentina to England. As if by divine providence, the fabled Hindenburg airship passed overhead during his voyage. Henderson and his fellow passengers watched in amazement as the massive airship hovered briefly to exchange wireless messages with the ship, and then sped off across the sky.

After arriving in Berlin several months later, Henderson presented his letters of credence to Adolph Hitler during a ceremony on May 7, 1937. The Hindenburg had been destroyed in a catastrophic fireball at Lakehurst, New Jersey the previous day, followed immediately by rumors of foul play. Henderson remarked upon Hitler’s “excited mental state,” and noted “It was always my fate to see him when he was under the stress of some emotion or other.”

Anthony Eden later reflected: “It was an international misfortune that we should have been represented in Berlin at this time by a man who, so far from warning the Nazis, was constantly making excuses for them, often in their company…. He grew to see himself as the man predesigned to make peace with the Nazis.”

Henderson was inclined to take Germany’s side on most significant issues, including a history book’s worth of actions against Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland.

Henderson found Hermann Göring – Hitler’s brutal lieutenant - to be “by far the most sympathetic” of the German leaders. And yet, despite their numerous interactions, “I do not flatter myself that in the long conversations which I had with him I ever modified his opinions.” Göring promised Henderson that if the Luftwaffe ever bombed London, and a bomb happened to land on Henderson’s head, “he would certainly send a special airplane to drop a wreath at my funeral.” Henderson, remarkably, appeared to believe and be charmed by this pledge. “And, if it did happen, I have no doubt he would do so.”

After attending Hitler’s annual spectacle in Nuremburg in 1938 against the wishes of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, Henderson ultimately felt compelled to file an urgent report. However, he realized that he had neglected to bring even a single sheet of paper. And so “I was obliged to use for the purpose the blank pages torn from some detective stories which I happened to have taken with me.”

American historian William L. Shirer, who wrote that: “worse than Henderson’s personal prejudices were his personal limitations,” also shared a description of Henderson by British historian Sir Lewis Namier: “Obtuse enough to be a menace and not stupid enough to be innocuous.”

Henderson's diplomatic career ended with the outbreak of war in September 1939. To his credit, Henderson’s book about his time as Ambassador to Germany carried the perfect title: Failure of a Mission. Even more to his credit, Henderson, who knew he was dying of cancer, donated the proceeds from sales of his book – totaling tens of thousands of pounds – to charity. He died on December 30, 1942.

Thanks for reading,

Bill