Interview with Craig Nelson - Author of "V is for Victory"

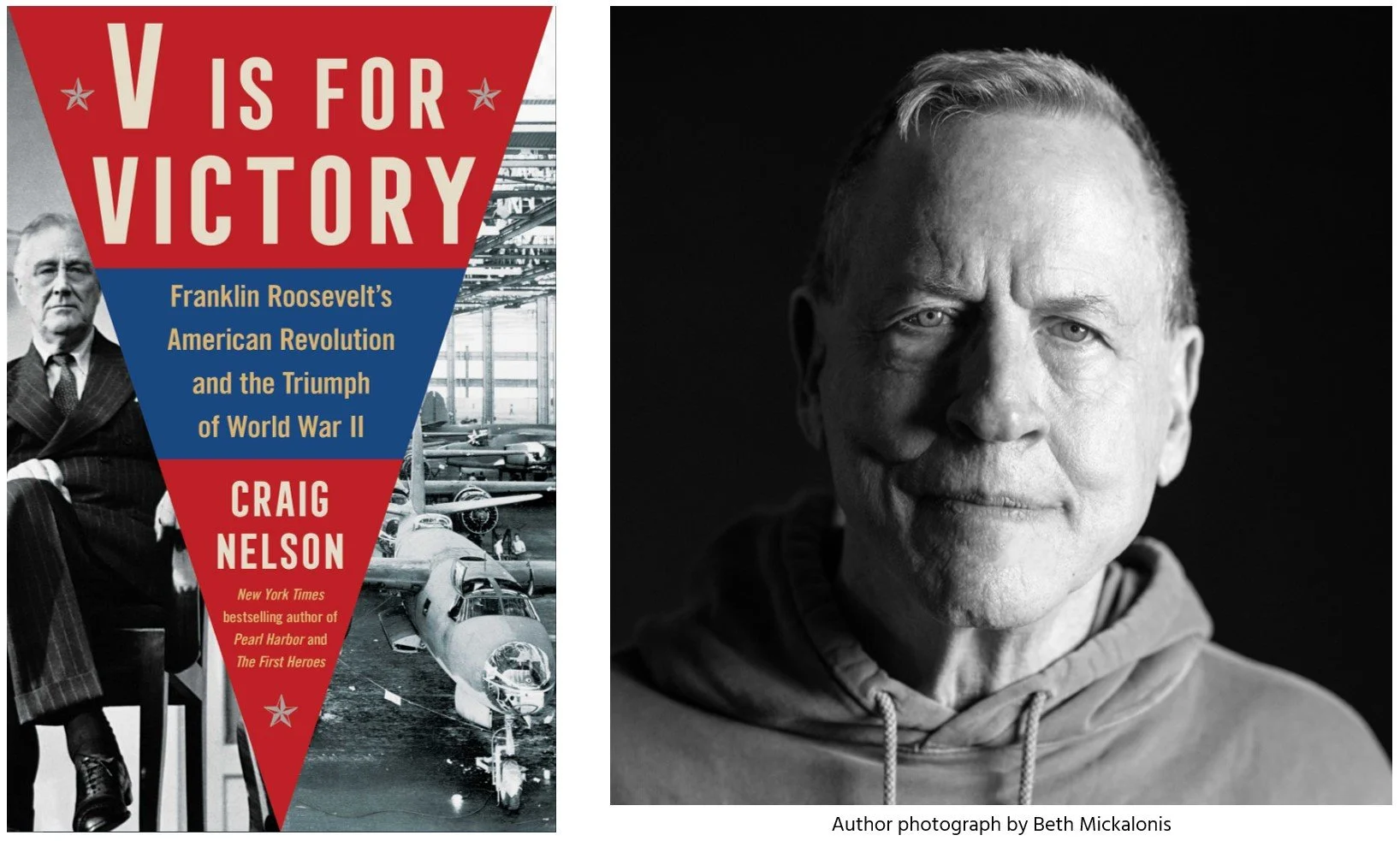

One of the unexpected blessings I've enjoyed during this book-writing adventure is the encouragement that I’ve received from well-established authors. Craig Nelson, who has written for Vanity Fair, The Wall Street Journal, Salon, Soldier of Fortune, National Geographic, Popular Science, Readers Digest, and other publications – and who has also written a half-dozen well-regarded nonfiction books - occasionally stokes my confidence with notes of encouragement. Craig’s newest book – V is for Victory: Franklin Roosevelt’s American Revolution and the Triumph of World War II – was published on May 23. Craig was kind enough to send me an advance copy, and then was even more kind in taking the time to answer a series of long-winded questions after I was enthralled by his story of how the unleashing of American enterprise helped win the War.

I think you will be surprised by some of the things you will learn in this interview. I hope you will be inspired to pick up a copy of V is for Victory.

You’ve written books about the Doolittle Raid, Thomas Paine, the First Men on the Moon, the Atomic Era, and – most recently – about Pearl Harbor. What led you to write a book that’s focused on Franklin D. Roosevelt and World War II?

I suddenly realized that that my mother and father’s life as parents, and grandparents, and professionals who’d achieved the height of their careers, was not the most significant thing that had ever happened to them. The most significant thing that had ever happened to them —and the very best years of their lives—was World War II. At the same time, I was randomly browsing through articles on military history, and came across some surprises. One said: “In wartime, logistics eats strategy for lunch,” which is pretty much the opposite of everything we’ve ever been told. Another mentioned Lincoln and Grant’s awful arithmetic: That, no matter how many battles the Confederates won, the Union, with its great advantage in supplies, would win the war.

All of this went into what turned out to be my third book on World War II, and it’s filled with things I never knew. The secret weapon to winning that war was the arsenal of democracy, which had many of its roots in the New Deal, and became the most successful union of U.S. government and enterprise in history. It’s the story of how Franklin Roosevelt’s policies (alongside his Great Debate with Charles Lindbergh) turned the United States upside down to create a wholly new country that would become both the lynchpin to defeating Hitler and Tojo, the leader of the West, and the global force that ensured that there would be no World War III. V is for Victory is the story of how, by transforming what Americans thought of themselves and what they could achieve, FDR ended the Great Depression; defeated the fascists of Germany, Italy, and Japan; birthed America’s middle-class affluence and consumer society; and turned the U.S. military into a worldwide titan—with the United States as the undisputed leader of world affairs.

During a 1932 campaign speech in Portland Oregon, FDR uttered a signature bare-knuckle charge: “Judge me by the enemies I have made.” Were there any enemies of his that you especially enjoyed researching and writing about?

After his baby was kidnapped and murdered, the most famous American in the world — Charles Lindbergh — fled the ravenous press photographers of the United States to live in England. He was invited to tour the Luftwaffe in 1938, and afterwards announced: “Germany now has the means of destroying London, Paris, and Prague if she wishes to do so. England and France together have not enough modern warplanes for effective defense or counterattack.” None of this was true, but it made the rest of the world believe that the Nazis were unbeatable, while inspiring the British and French to appease Hitler by giving him a piece of Czechoslovakia and Roosevelt to launch a government-led expansion of American aircraft production. This policy, the first step of the arsenal of democracy, became a remarkable success, In 1939, France and England bought 6,000 engines from East Hartford’s Pratt and Whitney, 1,300 Hudsons from Burbank’s Lockheed, 815 Marylands from Baltimore’s Glenn Martin, and 100 Wildcats from Bethpage’s Grumman, while U.S. airframe production doubled, and aircraft engine output tripled. By 1940, as the source of airpower for three nations, the United States outproduced Germany.

After watching FDR became the first president to be elected to a third term, Charles Lindbergh remembered saying to others who opposed Roosevelt that: “‘Democracy’ as we have known it is a thing of the past. . . . A political system based on universal franchise would not work in the United States. . . . One of the first steps must be to disenfranchise the Negro.” The conversation then turned to “the Jewish problem and how it could be handled in this country.” Lindbergh said that, along with Americans of British descent and Wall Street bankers, “were it not for the Jews in America, we would not be on the verge of war today. . . . The more feeling there is against the Jews, the closer they band together; and the more they band together, the more the feeling rises against them. . . . We are not a moderate people, once we get started, and an anti-Jewish movement might be considerably worse here than in Germany.”

You provide eye-opening perspective on just how unprepared America was for war by contrasting the size of America’s military with other nations in the late nine-thirties. Just how weak was America at that point?

On the morning of Franklin Roosevelt’s first inauguration as president in 1933, his predecessor, Herbert Hoover, had awakened to be told that over five thousand American banks had collapsed, taking their customers’ life savings with them. In four years, the stock market had fallen 85 percent and between 12 and 15 million Americans were jobless. Steel manufacturing was at 12 percent of capacity; half of Michigan’s automotive factories had shut down, and shipping across the Great Lakes had stopped. “We are at the end of our string,” Hoover admitted to an aide. “There is nothing more we can do.” Hoover was by this time so widely hated for doing so little about the country’s harrowing economy that a popular tale described the president asking a secretary to borrow a nickel to call a friend from a pay phone. The secretary gave him a dime and said, “Here, call them both.”

Across the two decades following World War I, a withdrawn and isolationist United States had stripped its military to the sinew. The U.S. Navy was so degraded in stature that Norfolk, Virginia, in time home to the largest naval base in the world, marked its parks in the 1930s with a sign: "No dogs or sailors.” American defenses fell to seventeenth in size in the world—smaller than Portugal’s, but bigger than Bulgaria’s—and during training, soldiers were forced to pretend to fight with broomsticks instead of rifles and with Good Humor ice cream trucks standing in for tanks while overhead, the air corps dropped bags of flour to imitate aerial assault, a practice so common it was called Betty Crocker bombs.

Before I started writing full time, I spent 30 years selling supply chain planning software. So, of course I was captivated by Chapter 10 in your book, “Have You Considered a Career in Supply Chain Management?” Can you share the gist of that chapter?

A nation’s fighting force can be described as a mix of soft flesh and hard matériel, with matériel being everything that is not human: uniforms, tents, cots, coats, guns, cannons, bullets, shells, radiophones, bandages and splints, seaworthy boats, working trucks, edible meals, potable water . . . an enormous amount of stuff, which, for World War II, numbered in quantities beyond human comprehension. After North Africa was taken, the United States did not dream of Wunderwaffen; it instead plodded to calculate how long it would take and what it would require to conquer Sicily, then Italy, then Germany; Saipan, then Okinawa, then Japan; just how many men would be required, how many Liberty ships, Higgins boats, Chrysler tanks, and Bantam cars; how many guns, tanks, trucks, planes, ships; how much ammunition, uniforms, shelter, food, transportation, medicines, gurneys, blankets, and boots. Military historian Fred Kaplan: “Amassing firepower—or any other military asset in large quantities—is a matter of mathematics: how to deliver x tons of material (troops, airplanes, bombs, supplies) across y miles in z amount of time, given the resources at hand. You can calculate the answer with precision and certainty.” The coordination of such a vast enterprise becoming known as supply-chain management, or logistics. Logistics became crucial in winning the war since it didn’t matter if you had ten times as many trucks as your enemy if those trucks were in the wrong place at the wrong time. As Gen. Robert Hilliard Barrow, USMC, said, “Amateurs talk about strategy and tactics. Professionals talk about logistics and sustainability in warfare.”

The history-changing victories of the Duke of Wellington, Alexander the Great, Hannibal, and the Mongols have all been attributed to logistics; Ulysses S. Grant is today admired for such tactics as using watered-down bales of hay and grain to reduce his ships’ vulnerability to catching fire from enemy cannonballs, with the hay and grain then used to feed horses and men after the battle was won. Military logistics is distinguished from corporate in that it combines fortifying one’s own supply lines while destroying the enemy’s, but surely soon enough a business-school guru will make his or her fortune by teaching this insight to eager divisional vice presidents.

Supply chain planners - who can be notoriously vague with their numbers (I used to be one, so I know) – will identify with the frustration of Bill Knudsen, who left his position as president of General Motors to take charge of wartime production. When he asked the military: “What do you want?,” the army replied that they wished to arm 400,000 men in three months, and another 800,000 men three months after that. When Knudsen replied that “he couldn’t work with such vague numbers, and “I want to know what kind of equipment you need for these men – and how many pieces of each kind …” “The army had no idea.” How was that massive disconnect eventually worked out?

It was and it wasn’t ;-) One of the earliest civilian/military traumas was a battle over buttons. The army specified its uniforms’ buttons to be made of horn or ivory, a tradition of many decades. Nelson now explained that, with the Nazis controlling Czechoslovakia, the United States no longer had a good source of horn, and between the world’s undergoing convulsions and the American military’s needing to immediately and exponentially grow, sourcing all the required horn and ivory from Africa and South America would mean delays and shortages. He recommended a good American company in Rochester that could provide excellent celluloid buttons in the great quantities needed.

The army replied, horn. Or ivory. Or nothing.

Military production was troubled both without and within. General Marshall after the war concluded that, of logistical failures, “the greatest by far was the critical shortage of landing craft.” Harry Hopkins explained the problem: “Estimates can be made and agreed to by all the top experts, and then decisions to go ahead are made by the president and the PM and all the generals and admirals and air marshals—and then, a few months later, somebody asks, ‘Where are all those landing craft?’ . . . And then you start investigating and it takes you weeks to find out that the orders have been deliberately stalled on the desk of some lieutenant commander or lieutenant colonel down on Constitution Avenue.”

I’ve always had this naïve notion that of course America’s auto plants readily adapted to the production of tanks and planes. But you share stories to show that the process of adapting was anything but simple. “Chrysler’s engineers judged the army’s tread design as working great on roads, but not in mud, their engine was air-cooled, but only when the air was cold, and the source of the vehicle’s chassis springs were turn-of-the-century railroad freight cars.” How monumental was the task of converting car plants (for example) to the production of tanks and planes?

Only those with experience in manufacturing understood the amount of time necessary to retool and transform a factory that churned out Model A’s into one mass-producing Flying Fortresses, which rested on one crucial category of production. Just as in modern times where robots make other robots, which make other robots, and so forth, and so on, manufacturing starts with the machines that make other machines—machine tools. Ranging in size from jewelry boxes to houses, machine tools are used to cut, shear, lathe, press, stamp, mill, scour, bore, drill, slice, plane, mold, trim, grind, and smooth metals, wood, cloth, and plastics; it took, for example, eighty-seven machine tools to manufacture a U.S. World War II propeller shaft. The delay that would lead to Knudsen’s downfall was in the manufacture of these machine tools, a process that was still an artisanal business, composed of a mere two hundred American firms, three of which dated back to the Revolutionary War. While under the Nazis between 1933 and 1938, Germany’s machine tool industry grew 800 percent to become the acknowledged global leader, the great majority of America’s machine tools had been made between 1850 and 1900 . . . forty to ninety years before Knudsen even arrived in DC.

You quote Dwight Eisenhower saying “Andrew Higgins … is the man who won the war for us.” Who is Andrew Higgins, and what was his contribution?

Andrew Jackson Higgins was the kind of outsize, big-tempered, bighearted all-American construction and engineering guy who drove himself and his employees to ever-greater heights of success .. if they didn’t die first. Before the arsenal, Higgins and his staff had engineered boats that could skim through the shallow drafts of his native Louisiana’s notorious swamps and bayous, and he was doing good business selling these Wonderboats to the Coast Guard for catching Prohibition rumrunners, but he could never get the navy to accept his designs over their own, even when his were clearly superior. He once spat out at a meeting that, “There are no officers, whether present in this room or otherwise in the navy, who know a goddamn thing about small-boat design, construction, or operation—but, by God, I do.” This was not the way to win naval hearts, but eventually the service gave him a contract to design a thirty-foot landing craft, as a test. When it succeeded, they ordered four more, as a test. When Higgins argued that their requirement of thirty feet was too short for the draw, the navy explained that, since some of their transports used davits designed for a thirty-footer, a thirty-footer it must be. Instead, Higgins built a model of the thirty-six footer he thought the navy should have and sent it to Norfolk. It was so clearly the superior of three competing designs that Higgins was contracted to build 335 of them. By the autumn of 1940, he had over $3 million in contracts.

Starting in Prohibition with fifty employees, Higgins now had sixteen hundred, and his shipyard had two assembly lines, one for white workers, the other for black, all trained by the company’s segregated schools. “Yes, we are going to build ships, by the strength of Americans, and we are going to tap that great reservoir of unskilled Negro labor and, by such educational training as we can give, equip him to do the job, with equal pay for the same work, and equal opportunity for advancement,” Higgins proclaimed.

All this industry meant that a nation that started at Pearl Harbor with 32 shipyards ended the war with 131, and produced, alongside thousands of merchant and warships, 82,028 landing craft (a quarter of which were courtesy of Higgins), meaning that, in June 1944, the nation could simultaneously launch two incomprehensibly enormous amphibious attacks, of thousands and thousands of vessels, against both Normandy and Saipan.

You noted that Germans, Japanese, and Americans were all sure they could win the war … for very different reasons. What was the basis for their confidence?

One military historian explained World War II as that the Germans thought they would win because of Prussian military training, and the Japanese thought they would win because of their never-surrender Bushido philosophy, and the Americans thought they would win because they had the most trucks. Trucks won.

Your book ends with a quote from FDR in which he warns of “the road to a third world war.” What would President Roosevelt make of the state of the world today?

I think he would be sorry that the United Nations hasn’t been more successful mediating such conflicts as Russia in Ukraine, and the various outburst of ethnic cleansing; and disappointed that the economics of the American middle class has been diminished. But he would be proud that the New Deal’s safety nets were still in effect, and that his post-war foundations have so far kept World War III from happening.

Thanks for reading. Thanks Craig!

Bill

PS: Craig’s book tour for V is for Victory kicks off this week with events at Arlington Library (in Arlington, VA) and at The Pentagon (in Washington, DC) on June 8 and June 9 respectively. To learn more about Craig, his body of work, and the remaining stops on his book tour, you can check out his website: http://www.craignelson.us/

PPS: With very few exceptions, I limit the frequency of this newsletter to once a month. It took a little bit of self-control to not immediately shout out about several cool things that happened this past month:

Joe Ciccarone had me as a guest on his "Built Not Born" podcast. I had an incredibly good time discussing Winston Churchill, the creative Process, and the art of sales with Joe.

I stashed a copy of Everybody Knows a Salesman Can't Write a Book in a Little Free Library near my home. The book is now gone - hopefully near the top of the reading pile of whoever took it home.

While we were away on a babysitting holiday weekend, a couple of neighbors texted the news that "Everybody Knows ..." was featured as one of the recommended summer reads by “authors with local ties” on the front page of the Living section in my hometown Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Sunday News. This of course means everybody in Lancaster County now has to read my book.